Aneto, just like every other mountain, is replete with history: that of the conquest of the highest mountain in the Pyrenees and of its first ascent.

At the easternmost point of the Maladeta Massif, Aneto looks more like the little brother of the peaks found further west, allowing it to go unnoticed when the area was being discovered by the first intrepid explorers to visit the area. It wasn’t until 1817 when Henri Reboul, backed up by advanced mathematical calculations, boldly claimed that it was Néthou, and not Monte Perdido as had been thought up until that time, that was the highest mountain in the Pyrenees. This discovery helped him launch a new career which saw him scour the highest parts of the Pyrenees.

Early attempts

1820 saw the first attempt to climb Aneto. The team of Leon Dufour and Henri Reboul, enlisting the assistance of local guides Martre and Barrau from nearby Bagnères-de-Luchon, decided to embark on that early effort. They departed from the French town and, while passing through the mountain pass at Benasque, they stopped to admire the mountain and they decided which route would take them to the top of the awe-inspiring Aneto. The chosen route was along an arête that appeared gentle and that rose up from Collado de Salenques. It was obvious, however, that things were not as they seemed. Once they reached the col, Salenques Arête quickly turned into a labyrinth of blockfields and gendarmes, and the four brave adventurers soon realised that any attempts to continue would be futile.

Seven years would pass before another attempt was made to reach the summit. This time, it was Étienne-Gabriel Arbanère, who started in the south, opting to stay far away from the enormous glaciers and fear-inducing mountain ranges found on the north face. He got as far as Brecha de Llosas before abandoning his attempt.

So, during that period, there were numerous efforts to reach the summit. While some routes proved to be better than others, and some would take the explorers closer to the peak, uncovering new glaciers and identifying new cols in the process, they all shared a similar fate: none of them managed to reach the very top.

First ascent

In 1842, a young Russian ex-military official by the name of Platon Chikhachyov set out to climb a number of the mythical Pyrenean peaks: Midi, Vignemal, Monte Perdido and, of course, the seemingly unattainable Aneto. It was not easy for him to find guides in Bagnères-de-Luchon who were willing to accompany him, as none wished to end up the same way as Barrau, who had died years before on Maladeta. By the midpoint of the summer season, he had managed to form the team that would go along with him. It was made up of the botanist Albert de Franqueville, two guides (Pierre Sanio and Jean Sors, known as Argarot) and two hunters (Bernard Arrazau and Pierre Redonnet). The entire group left for the mountain on 18 July 1842.

The route

The chosen itinerary passed through Benasque mountain pass, just as Dufour and Reboul had years prior, but this expedition would not make the same mistakes as the pioneers, and he instead decided to head for La Renclusa in Maladeta Massif. Once there, they veered to the south-east, where they crossed over the Brecha de Alba gap, from where they could see Ibón de Cregüeña, before continuing to Coronas. The purpose of such a roundabout route was to avoid the terrifying frozen slopes of Aneto’s north face.

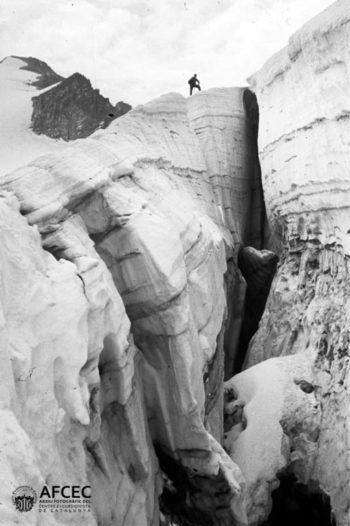

After two days of walking, they came across Ibón de Coronas, finding themselves one step closer to surpassing all who had gone before them. Even after reaching Collado de Coronas, they still had to face the giant icy slope that led to the summit, something they tried to avoid by ascending via the ridge. The decomposed rock and dense snow forced them into tackling the slopes of the glacier which, fortunately, was not such a daunting task after all, as it was covered with a good layer of snow, leaving their footprints clearly visible.

From the sub-peak, they managed to catch a glimpse of the summit through the fog. They had yet to reach it, and one final challenge lay ahead of them: crossing Puente de Mahoma, the narrow and vertigo-inducing horizontal section of ridge that separated them from the real peak, which would be baptised by Franqueville himself. Their successful ascent brought to a close one of the most important chapters in Pyrenean mountaineering history: Aneto had been summited for the very first time.

A stack of rocks and the first register containing the signatures of those triumphant few bore witness to the first successful ascent of the highest point in the Pyrenees.

| History | Getting there |